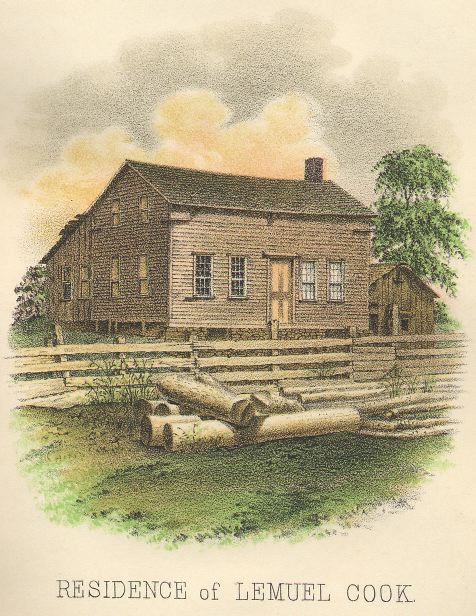

From the home of Mr. Waldo, the most distinguished, I passed to that of LEMUEL COOK, the oldest survivor of the Revolution. He lives in the town of Clarendon, (near Rochester,) Orleans county, New York. His age is one hundred and five years.

Mr. Cook was born in Northbury, Litchfield county, Connecticut, September 10, 1759. He enlisted at Cheshire, in that state, when only sixteen years old. He was mustered in “at Northampton, in the Bay State, 2nd Regiment, Light Dragoons, Sheldon, Col.; Stanton, Capt.” He served through the war, and was discharged in Danbury, June 12, 1784. The circumstances of his enlistment and early service he relates as follows:

‘When I applied to enlist, Captain Hallibud told me I was so small he couldn’t take me unless I would enlist for the war. The first time I smelt gunpowder was at Valentine’s Hill (West Chester, New York). A troop of British horse were coming. ‘Mount your horses in a minute,’ cried the colonel. I was on mine as quick as a squirrel. There were two fires – crash! Up came Darrow, good old soul! and said, ‘Lem, what do you think of gunpowder? Smell good to you?’

“The first time I was ordered on sentry was at Dobbs’ Ferry. A man came out of a barn and leveled his piece and fired. I felt the wind of the ball. A soldier near me said, ‘Lem, they mean you; go on the other side of the road.’ So I went over; and pretty soon another man came out of the barn and aimed and fired. He didn’t come near me. Soon another came out and fired. His ball lodged in my hat. By this time the firing had roused the camp; and a company of our troops came on one side, and a party of the French on the other; and they took the men in the barn prisoners, and brought them in. They were Cow Boys. This was the was the first time I saw the French in operation. They stepped as though on edge. They were a dreadful proud nation! When they brought the men in, one of them had the impudence to ask, ‘Is the man here we fired at just now?’ ‘Yes,’ said Major Tallmadge, ‘there he is, that boy.’ Then he told how they had each laid out a crown, and agreed that the one who brought me down should have the three. When he got through with his story, I stepped to my holster and took out my pistol, and walked up to him and said, ‘If I’ve been a mark to you for money, I’ll take my turn now. So, deliver your money, or your life!’ He handed over four crowns, and I got three more from the other two.”

Mr. Cook was at the battle of Brandywine and at Cornwallis’ surrender. Of the latter he gives the following account: “It was reported Washington was going to storm New York. We had made a by-law in our regiment that every man should stick to his horse: if his horse went, he should go with him. I was waiter for the quartermaster; and so had a chance to keep my horse in good condition. Baron Steuben was mustermaster. He had us called out to select men and horses fit for service. When he came to me he said, ‘Young man, how old are you?’ I told him. ‘Be on the ground to-morrow morning at nine o’clock,’ said he. My colonel didn’t like to have me go. ‘You’ll see,’ said he ‘they’ll call for him to-morrow morning.’ But they said if we had a law, we must abide by it. Next morning, old Steuben had got my name. There were eighteen out of the regiment. ‘Be on the ground,’ said he, ‘to-morrow morning with two days’ provisions.’ ‘You’re a fool,’ said the rest; ‘they’re going to storm New York.’ No more idea of it than of going to Flanders. My horse was a bay, and pretty. Next morning I was the second on parade. We marched off towards White Plains, Then, ‘left wheel,’ and struck right north. Got to King’s Ferry, below Tarrytown. There were boats, scows, &c. We went right across into the Jerseys. That night I stood with my back to a tree. Then we went on to the head of Elk. There the French were. It was dusty; ‘peared to me I should have choked to death. One of ’em handed me his canteen; ‘Lem,’ said he, take a good horn – we’re going to march all night. I didn’t know what it was, so I took a full drink. It Iiked to have strangled me. Then we were in Virginia. There wasn’t much fighting. Cornwallis tried to force his way north to New York; but fell into the arms of Lafayette, and he drove him back. Old Rochambeau told ’em, ‘I’ll land five hundred from the fleet, against your eight hundred.’ But they darsn’t. We were on a kind of a side hill. We had plaguey little to eat and nothing to drink under heaven. We hove up some brush to keep the flies off. Washington ordered that there should be no laughing at the British; said it was bad enough to have to surrender without being insulted. The army came out with guns clubbed on their backs. They were paraded on a great smooth lot, and there they stacked their arms. Then came the devil – old women, and all (camp followers). One said, ‘I wonder if the d—-d Yankees will give me any bread.’ The horses were starved out. Washington turned out with his horses and helped ’em up the hill. When they see the artillery, they said, ‘There, them’s the very artillery that belonged to Burgoyne.’ Greene come from the southard: the awfullest set you ever see. Some, I should presume, had a pint of lice on ’em. No boots nor shoes.”

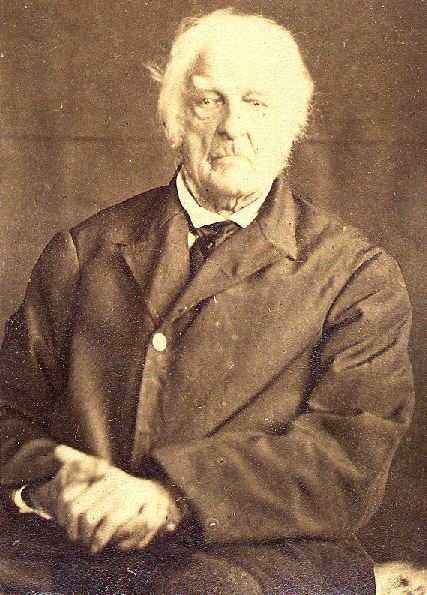

The old man’s talk is very broken and fragmentary. He recalls the past slowly, and with difficulty; but when he has fixed his mind upon it, all seems to come up clear. His articulation, also, is very imperfect; so that it is with difficulty that his story can be made out. Much of his experience in the war seems gone from him; and in conversation with him he’ has to be left to the course of his own thoughts, inquiries and suggestions appearing to confuse him. At the close of the war, he married Hannah Curtis, of Cheshire, Connecticut; and lived a while in that vicinity; after which he removed to Utica, New York. There he had frequent encounters with the Indians who still infested the region. One with whom he had some difficulty about cattle, at one time assailed him at a public house, as he was on his way home, coming at him with great fury, with a drawn knife. Mr. Cook was unarmed; but catching up a chair he presented it as a shield against the Indian’s thrusts, till help appeared. He says he never knew what fear was, and always declared that no man should take him prisoner alive. His frame is large, his presence commanding; and in his prime he must have possessed prodigious strength. He has evidently been a man of most resolute spirit; the old determination still manifesting itself in his look and words. His voice, the full power of which he still retains, is marvellous for its volume and strength. Speaking of the present war, he said, in his strong tones, at the same time bringing down his cane with force upon the floor, “it is terrible; but, terrible as it is, the rebellion must be put down!” He still walks comfortably with the help of a cane; and with the aid of glasses reads his “book,” as he calls the Bible. He is fond of company, loves a joke, and is good-natured in a rough sort of way. He likes to relate his experiences in the army and among the indians. He has voted the Democratic ticket since the organization of the government, supposing that it still represents the same party that it did in Jefferson’s time. His pension, before its increase, was one hundred dollars. It is now two hundred dollars. The old man’s health is comfortably good; and he enjoys life as much as could be expected at his great age. His home, at present, is with a son, whose wife, especially, seems to take kind and tender care of him. Altogether, he is a noble old man; and long may it yet be before his name shall be missed from the roll of his country’s deliverers.

See Also “The Last Men of the Revolution-Daniel Waldo”